Tropicalis Universalis is a collection of greatly varied expressions and practices, all manifestos of a new sensibility. The tropicalist movement emerged at the onset of the 21st century in the great metropolises found between the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn. It is the expression of a new approach to life, of a new modus vivendi, of a new relationship with reality. A new way to see constructs, art, architecture and material objects. A new urban condition.

credits: Thiago Souto, Astúrias, Guarujá-SP

This way of thinking and feeling takes reality as its starting point and goes on to invent a new landscape: the tropical metropolis. It forges new life forms to set against the ailing and failing modernist or post-modernist project.

It is resolute in embracing the warmth of tropical life and its social ethos. It is an antidote to the pallor of post-modernism. Its intensity is life-awakening.

Tropicalism is a bundle of practices, and entropism is the banner under which it marches. Tropicalism conceives architecture as the

very expression of entropism. It recasts the lifeless remains of modernism into the life-forming mold of entropism, ready to firm up in the fire of creativity.

This architecture is not the expression of order, nor the expression of chaos. It expresses the burning desire to take up arms against a society with too great an order. Is it the expression of Oscar Niemeyer’s sopro,[1] the expression of the La condition humaine (1933), written by his friend, André Malraux.

Tropicalisation

Extract from the Yearbook of the National College of Architecture of Versailles. Triptyque, 2011.

The term tropicalisation is used to describe the state of Westerners who have lived in the Tropics and who have difficulty readapting to their home country.

In urbanism and in architecture, tropicalisation can also mean a form of construction in large urban regions located between the two imaginary lines known as the Cancer and Capricorn tropics.

Tropicalisation, until recently considered exotic, has become a dominant concept due to the importance that these tropical cities have acquired in the last few decades.

It is completely contrary to the new urban and architectural paradigms of contemporary cities.

Tropicalisation can consist of, according to the practitioner:

defying the “artificial abyss” of contemporary cities;

promoting human experience over landscape viewing;

favouring entropic systems, the corruption materials;

showing the passage of time and ageing;

favouring the exuberant and the immoral;

not being afraid of the hybrid or the clumsy;

adopting the study of sustainable unfamiliarity as a creative means and the limit of knowledge, or lack thereof, as a facet to study;

preferring the wild to the technological;

forget the verdict as to being good or bad taste;

privileging experimentation and improvisation;

considering each project as a living being;

designing projects that are more creature than creation;

seeking for projects to acquire a certain autonomy, for them to be foreign to their designers, for them to escape.

In policy and empty form:

enveloping architecture with lush vegetation;

abandoning air travel altogether rather than finding non-polluting ways to fly;

evoking primitive myth over nostalgia.

Famous names in tropicalisation: Hélio Oiticica, Oswald de Andrade, Suely Rolnik, Roche & Sie, Lina Bo Bardi, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Neri Oxman, Friedensreich Hundertwasser, Paul Virilio and Claude Parent.

Yes, somos Tropicalists

Triptyque, 2010

We are Tropicalists in many ways.

First, we are not in any discernable way strictly European or Brazilian. We stand for the first definition of tropicalisation, “the condition of Westerners who find it difficult to readapt once back in their native countries”.

Second, we are in the clutches of the problems of the new urban world order and in particular, of one of its most widespread and virulent manifestations: tropical metropolises. Our architecture, almost in spite of ourselves, is bound up with the dialectic of the tropical metropolis, with the challenge it poses to architects and town planners, a challenge that those of us who live in a metropolis cannot avoid.

Third, we have been devoured by tropical modernity. Like artist Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, we have developed a fascination for an “urban landscape charged with sensuousness” where “certain forms of architectural modernity in the field of architecture (but also in literature, cinematography and music), are more alive, more intense, more experimental in a tropical environment, when associated with robust and lush vegetation, with intense lights and skies, with extreme climates.”

Finally, although we feel we have been ingested by Brazilian and, therefore, tropical culture, in return, we like to conceive of the contemporary metropolis through the notion of cultural cannibalism, in particular through the dialectic set up between Oswald de Andrade’s Anthropophagic Manifesto and the concepts of Suely Rolniks’s Anthropophagic Zombie. In tropical cities, how can we create the living soul of cities that are nourished by the world about them, without falling into the facile falsehoods of hybridizing concepts in a context of globalization? How do we escape the twin perils of “symbolic ingestion by the colonialist and his culture” and of “a contemporary anthropophagic experience, doomed to perdition in the jungle of finance capitalism”?

credits: Triptyque

credits: Triptyque

White Cube

Instalação no Museu V&A. Triptyque, 2010.

The hut developed expresses the atelier’s wish to work on a project that, under the sign of primitive design, embraces the pure form’s premise. It is a piece that initially does not put on display a powerful cultural element, but dialogues directly to an element of vernacular English architecture — the thatched roof — where materials, forms and traditional structures are explored minutely in the set.

Finally, the straw utilized in the thatched roof manifests the organic spirit that is imparted on those who lay eyes on it. Bearing a resemblance to a hedgehog or a porcupine, the body is covered in straw and then trimmed to achieve the shape of the desired design-less cube. And it’s on it that drips, at a set time and frequency, a white liquid stored in two tanks affixed at the top of the creature.

Thus, as in changing of solid, liquid or gaseous states, the creature offers the transmutation of the thatched roof’s traditional aspect to the creature’s state of intervention, from the growth of the wood structure, the opening of its slot, the budding straw that serves as cover, and the slow flooding of the white liquid on its coat.

credits: Leonardo Finotti

Natural Artificial

Pavillion at Inhotim. Triptyque, 2012.

The Inhotim Cultural Institute, based in Minas Gerais is one of the new places devoted to contemporary art. Triptyque conceived four of its spaces: Oca, Cube, Omelete, Tree Walk and an Exhibition Hall, both located in strategic places of the Institute. The south american writers Jorge Luis Borges, Gabriel García Marquez and the fantastic realism were visited for the concept formulation of these projects, for proposing a sensorial experience between the natural and the artificial.

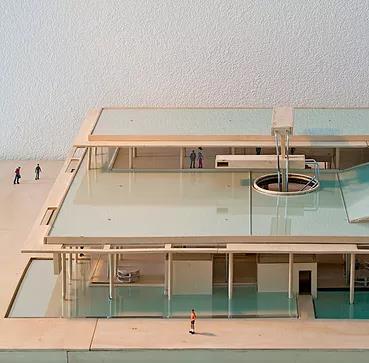

Water

Osny’s Media library, France. Triptyque (with Bidard & Raissi), 2014.

Osny’s Media library is not only just the still image of its structure, but the expression of the dynamic heating and cooling system that irrigates and brings the building to life.

The project’s innovative aspect is in opting for a tempered and recycled water system on the roof, cascading into ponds that cover the entirety of the building.

This, depending on the season, heats or cools the building.

This solution is based on low-tech building processes that demand a small investment, both in construction and maintenance.

The proposal, due to possible geo thermal means, will take care of temperature control.

The water reservoir, the central figure of the fluid circuit becomes a sign emerging from the media library.

This technical concept emphasizes space fluidity and allows for evolution of the layout (such as media type changes, program based evolution, etc.). The building is designed as a continuation of the public space, goes for maximum transparency, opened to all and easily accessible.

Sverre Fehn

Mouldiness

Manifesto

against

Rationalism

in Architecture

Friedensreich Hundertwasser, 1958.

“When rust sets in on a razor blade, when a wall starts to get mouldy, when moss grows in a corner of a room, rounding its geometric angles, we should be glad because, together with the microbes and fungi, life is moving into the house and through this process we can more consciously become witnesses of architectural changes from which we have much to learn.

The irresponsible vandalism of the constructive, functional architects is well known. They simply wanted to tear down the beautiful stucco-facade houses of the 1890s and Art Nouveau and put up their own empty structures. Take Le Corbusier, who wanted to level Paris completely in order to erect his straight-line, monstrous constructions.

[…]

It is time for industry to recognise its fundamental mission, which is to engage in creative moulding! It is now the task of industry to engender in its specialists, engineers and doctors a feeling of moral responsibility towards moulding.

This moral responsibility towards creative moulding and critical weathering must already be established in education laws. Only the engineers and scientists who are capable of living in mould and producing mould creatively will be the masters of tomorrow.

And only after creative moulding, from which we have much to learn, will a new and wonderful architecture come about”.

Sverre Fehn

The Universitas Project

Emilio Ambasz. MoMA, 2006.

“In our efforts to master nature-as-found, we have created a second nature, man-made nature, which contrasts endlessly with given nature. We need to redefine all aspects of material production, an overbearing protagonist of man-made nature, but to do so we need first to redefine the philosophical meaning of a contemporary nature.”

credits: Triptyque, FRAC Installation

Accursed cities

Extract from Frédéric Sayer’s doctoral thesis. La Sorbonne, 2007.

“On the other hand, the myth of the accursed city came into currency in the 1970s. The singular feature of this myth is that it generates idols or false myths. These simulacrums are objects without history, the irrevocable breaking apart of sacred from profane. The accursed and universal blight of anti-myth, which feeds on its own substance in an orgy of self-destruction. This myth is cannibal.

Hence urban construction itself now lies under a curse. Hence the anguish that gnaws at our civilization. A curse that was conjured up when all hope was lost in technical progress, when the concentration camps came to light in 1945. A universal malediction, that is the cannibalistic symbol of the loss of our ability to symbolize. Worse even than the curse of God raining down on the legendary city of shame, is the very absence of divine utterance — the deafening silence of urban noise. The background sound of the city is a fury that signifies nothing. The earlier image of the wall of silence is eloquent. So too is the image of the surface without depth. In sum, to be human is to have body, and yet be void. We occupy space, but are open through our orifices.”

The FRAC

Pavilion, Orleans, France. Triptyque, 2011.

We designed a structure that uses water as a mainly poetic element. It proposes a unique experience for the visitor who penetrates with a rain cape into a device, where water seems to flow naturally. In fact equipped with basic pumps, the “machine” guides the flow in a theatrical display, conjuring the image of “tulips” used in artificial lakes. The aim is to offer from both inside and outside the pavilion an architectural perspective exclusively composed of water.

credits: Unknown

‘I am only interested in what’s not mine.

The law of men. The law of the cannibal’

Francesco Manacorda and Pablo León de la Barra.

Os Barbicanistas, 2006.

“1. Manifest of inverted anthropophagy

Os Barbicanistas aims to explore the possibility of complementing, via a geographical and theoretical inversion, the crucial notion of Anthropophagy as a possible synonymous of the Brazilian interpretation of Modernism. Such a response to modernity constituted a type of rebellion to the pristine language of the avant-garde meant to be international and universal. A tendency of this nature entails a move towards a pop vernacular meant to assert, yet more forcefully, one’s own identity. In his Manifesto of Anthropophagy Oswald de Andrade encouraged assimilation and cultural digestion as the key Brazilian modernist strategy in order to fight cultural submission implied in internationalism.

[…]

The imperative is to cultivate and grow pockets of brutal tropicalism in the core of globalized culture including from climate to social atmospheres and conditions.

Due to its perfect location, Os Barbicanistas will take place in the Barbican’s Conservatory in the Barbican Centre, a tropical nucleus in the heart of the epitome of brutalist architecture. This ideal location combines an enclosed organic space within an advanced modernist concrete landscape, representing an island of condensed natural exuberance.

[…]

This hypothesis implies the assumption that ‘Tropical truth’ could arguably be considered as much a universal language as modernism pretended to be; neither of those is more international, both of them are languages, mainly tools to articulate desires and concerns. While Modernism assumed different declinations, translations and adaptations according to the country that made it their own, Tropicália infiltrates a melancholy within every social and cultural industry, vernacularising the concerns of Brazilian modernism from Andrade to Oiticica, from Lina Bo Bardi to Glauber Rocha. Such a model seems more appropriate as a strategy of resistance today as — differently from the sixties when the US and Eurocentric models were opposed to national ones — today reverse anthropophagy represents a more adequate model to oppose globalization within the culture industry.”

credits: Triptyque, RB Project

Generic City

Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau, 1995.

“In the Generic City, because the crust of this civilization is so thin, and through its immanent tropicality, the vegetal is transformed into Edenic Residue, the main carrier of its identity: a hybrid of politics and landscape. At the same time refuge of the illegal, the uncontrollable, and subject of endless manipulation, it represents a simultaneous triumph of the manicured and the primeval. Its immoral lushness compensates for the Generic City’s other poverties. Supremely inorganic, the organic is the Generic City’s strongest myth.”

credits: Romulo Fialdini

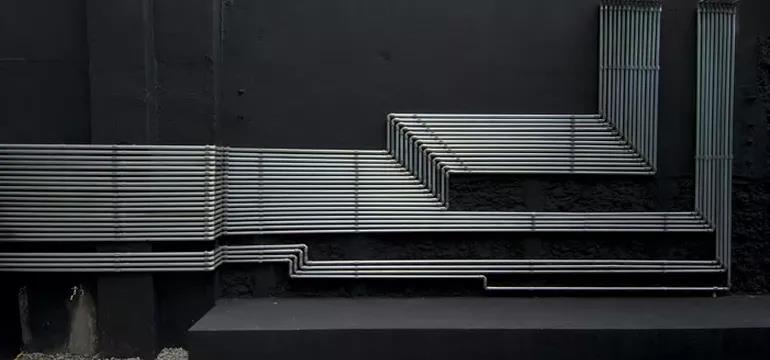

Pipelight

Triptyque, São Paulo, 2008.

The Pipe Light lighting system was created as a product that would have a form similar to that of a living organism that invades and takes over the entire house, as would climbing ivy, and in doing so, becomes a bridge between art and design. Quite on the contrary to its inspiration (Harmonia 57), which undergoes photosynthesis; the Pipelight system feeds off darkness.

These lanterns also reveal the technical design that is hidden between the walls, using pipes and other existing industrial components.

The drawings that are formed by the grey pipes and the lights on the black walls are combined into a monochromatic design, favoring the rustic features of the building. The lights breathe life into the drawing, transforming its simplicity into a complex interchange between bright and dark.

“Tristes tropiques”

Claude Lévi-Strauss, Tristes tropiques, 1955.

“The cities of the New World have one characteristic in common: that they pass from first youth to decrepitude with no intermediary stage. […] …as these are new cities, and cities whose newness is their whole being and their justification, I find it difficult to forgive them for not staying new for ever. The older a European city is, the more highly we regard it; in America, every year brings with it an element of disgrace. For they are not merely ‘newly built’; they are built for renewal, and the sooner the better. When a new quarter is run up it doesn’t look like a city, as we understand the word; it’s too brilliant, too new, too high-spirited. It reminds us more of our fairgrounds and temporary international exhibitions. But these are buildings that stay up long after our exhibitions would have closed, and they don’t last well: facades begin to peel off, rain and soot leave their marks, the style goes out of fashion, and the original lay-out is undermined when someone loses patience and tears down the building next door. It is not a case of new dries contrasted with old, but rather of cities whose cycle of evolution is very rapid as against others whose cycle of evolution is slow. Certain European cities are dying off slowly and peacefully; the cities of the New World have a perpetual high temperature, a chronic illness which prevents them, for all their everlasting youthfulness, from ever being entirely well. […]

What astonished me in São Paulo in 1935, and in New York and Chicago in 1941, was not their newness, but the rapidity with which time’s ravages had set in.”

Beton Hala Waterfront Center

Cultural center, Belgrade, Triptyque, 2011.

The waterfront center is a connection building between the river and the city. We conceived the Beton Hala Waterfront Center as a living architecture. Our intention was to bring the river to the city in order to create a physical mix between the latter and the water.

There is continuity in the landscape, an emphasis on the views. The water is omnipresent in the architecture of the building; it multiplies views in a kaleidoscopic manner. Water is also flowing from the building, glistening, creating a liquid belvedere of sorts.

There is a new relation between architecture, technology, nature and human resources. The new deal about sustainability and humanity demands transparency and affects our vision of architecture.

credits: Installation Rio de Janeiro, Jean Pascal Flavien, "Viewer", 2008

“Opened doors”

Christian de Portzamparc, Portes ouvertes, in revue Urbanisme n.337, 07/2004.

“I had been studying and reflecting about the peculiar nature of São Paulo, about what I call “the specificity of the paulista fabric”. In other words, there is a historical basis, a field of one or two story houses and sometimes small towers. If someone owns three parcels of land he has the right to build a small tower and then builds one to rent out. When we fly over the city by helicopter we can see this very interesting hybrid fabric of two cities, one horizontal and another vertical. For kilometers, from the central area to the horizon, this sheet goes; it possesses some beauty and coherency born from a basic division of the land and a very simple sanitarian perspective. Then we have this city with two heights. In it the vertical dimension is never disturbing, does not provide an excess of shade and gives the city and its streets a double height gain, with commerce occupying low houses, shaping what we might call a “narrative line” with those small towers above.

In neighborhoods like Higienópolis — created in the twenties — there is some freedom between street and building. There I find again, a little, open blocks in a variety of scales, with buildings from the thirties and, later, a more hybrid situation with some taller buildings. At the end, the results are almost perfect. These are neighborhoods where it is possible to live a good middle-class life, with no poverty or luxury. This hybrid side is surprising in São Paulo, a dense and complex city.”

credits: Leonardo Finotti

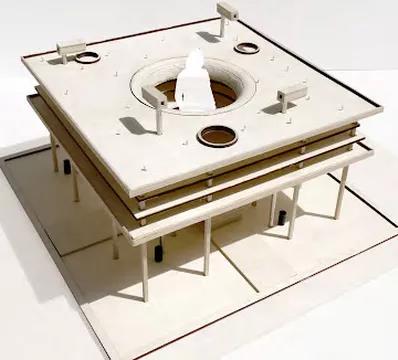

Contemplating the Void

Exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum, New York, Triptyque, 2010.

In 2010, the Guggenheim Museum celebrated its 50th anniversary by opening its doors to artists and architects to react to the “eccentric and organic design” of the Museum, and more specifically on the Rotunda, the Museum’s central void, for an exhibition called Contemplating the Void.

We responded to that invitation by creating gigantic and fantastic beings made of organic material we dubbed Creatures. Breaking free from the museum’s boundaries, the creatures spread throughout the vast urban area of the North American metropolis, New York City. They all intertwine in a huge set of membranes, becoming then a single body that returns to the original building and occupies the edges of the void. As it is with the history of modern cities, these creatures take on different personalities and draw attention to neighboring sites, connecting via straight lines or curves. The observation vis-à-vis the representativeness of these forms, and their connections, reveals the space’s organic nature and even the movements of human beings who live, work, and/or move in the city. In any direction of the proposed model, the emanating energy returns to the Guggenheim void. Human beings are the active subjects of this experience, and each creature spread on the model has strength at its core. The intense irradiation transforms, then, into a big party where music, art, and conversation end, in the best way, as the meaning of all this energy.

In a utopia of tropicalisation within a contemporary city, we dreamt a daring dream: spreading the meeting point to other areas of the city, overcoming the limits of the void, surpassing the physical boundaries of the building and, then, taking over the immense territory of the city. Therefore, other voids spread through the urban stain and amplify the noise and radiation of the energy originally coming from the museum’s interspaces.

credits: Rafael Assef

Anthropophagic Zombies

Extract from Anthropophagic Zombies, Suely Rolnik, 2011.

“If we now focus our micropolitical gaze on Brazil, we will discover an even more specific feature in the process of neoliberalism’s installation, and of its cloning of the movements of the 1960s-70s. In Brazil those movements had a particularity, because of a reactivation of a certain cultural tradition of the country, which had come to be known as “anthropophagy”. Some of the characteristics of this tradition are: the absence of an absolute and stable identification with any particular repertory and the non-existence of any blind obedience to established rules, generating a plasticity in the contours of subjectivity (instead of identities); an opening to the incorporation of new universes, accompanied by a freedom of hybridization (instead of a truth-value assigned to a particular repertory); an agility of experimentation and improvisation to create territories and their respective cartographies (instead of fixed territories authorized by stable and predetermined languages) — all of this carried out with grace, joy and spontaneity.

[…]

Now, the same singularity that gave such strength to the counter-cultural movements in Brazil also tended to aggravate the cloning of those movements carried out by neoliberalism. The anthropophagical savoir-faire of the Brazilians gives them a special facility for adapting to the new times. The country’s elites and middle classes are absolutely dazzled by being so contemporary, so up-to-date on the international scene of the new post-identity subjectivities, so well-equipped to live out this post-Fordist flexibility (which, for example, makes them international champions in advertising and positions them high in the world ranking of media strategies).[1] But this is only the form taken by the voluptuous and alienated abandonment to the neoliberal regime in its local Brazilian version, making its inhabitants, especially the city-dwellers, into veritable anthropophagic zombies.”

[1]Brazilian television occupies an important place on the international scene. A sign of the times: series produced by the Globo network are now broadcast in over 200 countries.

A Huge Void

Biennial of Shenzhen, China, Triptyque, 2009.

For the challenge of projecting the engagement between the Chinese cities of Hong Kong and Shenzhen, Triptyque atelier adopted a scope that extends the discussion that arose when its architects were invited by Guggenheim Museum, in New York, to create a dream intervention for a void in a Manhattan building.

For both the American and Chinese cases, the architects propose an understanding of the contemporary city and the construction of new architectural structures from the identification of the city as gigantic organic creatures. The fluid shape of these beings represents the vital energy of the metropolis and its citizens. It overcomes the strength that exists in the purely mineral space design, and is the essence of urbanity in accordance with the adopted architectural scope.

As in modern cities, these creatures take on different personalities and grow continuously, drawing attention to neighboring sites, and connecting via straight lines or curves. The observation of these forms and their connections reveals its representativeness, which is the organic nature of space and the movement of human beings who live, work and/or move the cities.

Precisely in the center of this movement arises the target of the architects’ scope regarding the integration between Shenzhen and Hong Kong: a huge void, seen geographically in the area surrounding Ma Chau River, where the creature’s energies associate and transmute into membranes that define the unique and vast area of integration.

The organic nature of the creatures, their tracks and membranes represents, in truth, the forces of the metropolis and its citizens. In any sense of proposed model, the energy returns to the void where intense radiation formats, as does a feast of music, art and conversation.

In the case of Chinese cities, Triptyque’s imagination goes beyond Ma Chau River and takes on the form of a pavilion whose deployment occurs in the middle of Shenzhen civic center. No more than 30 linear kilometers separate this site from the prosperous commercial and financial center of neighboring Hong Kong, population transit between cities, however, increased only after 1999 when political and military control of the former English protectorate returned to China.

credits: Triptyque

I’ve heard about

Philippe Morel, I’ve heard about (C), R&Sie(n) with Benoît

Durandin, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris/ARC, 2005.

“There’s no lamentation, no ‘puerile critique of society’[1], no individualist primitivism, no worship of the artisanal, no pathetic architectural recycling of waste materials, not to mention scolding of the ugliness of the built environment.”

[1]G. Benn: ‘Puerile critique of society’ also comprehends provincial rebellion: ‘In the Mediterranean, since that’s the location of your question. I’ve tried to say no to imperialism, brilliance and aluminum, and not to be a fellow-traveller of a generic, globalized trend. Marseille is not the flat country cynical urbanists dream of.” R. Riccioti, www.archicool, October 6, 2004.

From Skin to Flesh

Ricardo de Ostos, exhibition at the Eduardo Fernandes Gallery,

São Paulo, (Triptyque+Vazio+Spacegroup), 2011.

“From Skin to Flesh came alive already zombied after a short flowering in the urban shores. Age, relationship status and home address are all on its Facebook account. Born as a creature from architects parents it endured the novelty of being a crossbreed between proto-architecture and tropical fever. Living as a creature its life was an experimentation in being playful, interactive and sometimes participative. Another unique creature, Frankenstein paid tribute to From Skin:

‘We are unfashioned creatures, but half made up, if one wiser, better, dearer than ourselves…’

Once labelled an unfinished business of pure process and the creation of lunatic urban scientist it reacted to the blossoming of everyday pollution and cacophony of the city of São Paulo. Its skin going rot was its greatest achievement. It certainly changed. No being architecture, but half-bred it embraced the dirty and the everyday caresses of urban adventures and tropical sweat. Rotting and pus bare flesh gave its half-unfinished building skin a new unique coat. A concrete slab also paid homage: From Skin was poisoned as it succumbed to its need for interactaction. I guess being a half-alive zombie is a quality in the architectural scene nowadays. God knows why.”

credits: Triptyque

Brazilwood Manifesto

Oswald de Andrade, 1928.

“Only Cannibalism unites us. Socially. Economically. Philosophically.

The unique law of the world.The disguised expression of all individualisms, all collectivisms.Of all religions.Of all peace treaties.

Tupi or not tupi that is the question.

Against all catechisms.And against the mother of the Gracos.

I am only interested in what’s not mine. The law of men.The law of the cannibal.

We are tired of all those suspicious Catholic husbands in plays. Freud finished off the enigma of woman and the other recent psychological seers.

What dominated over truth was clothing, an impermeable layer between the interior world and the exterior world. Reaction against people in clothes. The American cinema will tell us about this.

Sons of the sun, mother of living creatures. Fiercely met and loved, with all the hypocrisy of longing: importation, exchange, and tourists. In the country of the big snake.

It’s because we never had grammatical structures or collections of old vegetables. And we never knew urban from suburban, frontier country from continental. Lazy on the world map of Brazil.

One participating consciousness, one religious rhythm.

Against all the importers of canned conscience.For the palpable existence of life. And let Lévy-Bruhl go study prelogical mentality…”